Shem Hotep ("I go in peace").

Splendor in Medieval Africa A visit to Mali's medieval past.

As an amateur medievalist, I have become keenly aware of how the history of Europe in the middle ages is often misunderstood or dismissed by otherwise intelligent, educated individuals. The medieval era of those nations outside of Europe is doubly ignored, first for its disreputable time frame (the "dark ages"), and then for its apparent lack of direct impact on modern western society.

Such is the case with Africa in the middle ages, a fascinating field of study that suffers from the further insult of racism. With the unavoidable exception of Egypt, the history of Africa before the incursion of Europeans has in the past been dismissed, erroneously and at times deliberately, as inconsequential to the development of modern society. Fortunately, some scholars are working to correct this grave error. The study of medieval African societies has value, not only because we can learn from all civilizations in all time frames, but because these societies reflected and influenced a myriad of cultures that, due to the Diaspora that began in the 16th century, have spread throughout the modern world.

One of these fascinating and near-forgotten societies is the medieval Kingdom of Mali, which thrived as a dominant power in west Africa from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century. Founded by the Mande-speaking Mandinka2 people, early Mali was governed by a council of caste-leaders who chose a "mansa" to rule. In time, the position of mansa evolved into a more powerful role similar to a king or emperor.

According to tradition, Mali was suffering from a fearful drought when a visitor told the king, Mansa Barmandana, that the drought would break if he converted to Islam. This he did, and as predicted the drought did end. Other Mandinkans followed the king's lead and converted as well, but the mansa did not force a conversion, and many retained their Mandinkan beliefs. This religious freedom would remain throughout the centuries to come as Mali emerged as a powerful state.

The man primarily responsible for Mali's rise to prominence is Sundiata Keita. Although his life and deeds have taken on legendary proportions, Sundiata was no myth but a talented military leader. He led a successful rebellion against the oppressive rule of Sumanguru, the Susu leader who had taken control of the Ghanaian Empire. After the Susu downfall, Sundiata laid claim to the lucrative gold and salt trade that had been so significant to Ghanaian prosperity. As mansa, he established a cultural exchange system whereby the sons and daughters of prominent leaders would spend time in foreign courts, thus promoting understanding and a better chance of peace among nations.

Upon Sundiata's death in 1255 his son, Wali, not only continued his work but made great strides in agricultural development. Under Mansa Wali's rule, competition was encouraged among trading centers such as Timbuktu and Jenne, strengthening their economic positions and allowing them to develop into important centers of culture.

Next to Sundiata, the most well-known and possibly the greatest ruler of Mali was Mansa Musa. During his 25-year reign, Musa doubled the territory of the Malian Empire and tripled its trade. Because he was a devout Muslim, Musa made a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324, astonishing the peoples he visited with his wealth and generosity. So much gold did Musa introduce into circulation in the middle east that it took about a dozen years for the economy to recover.

Gold was not the only form of Malian riches. Early Mandinka society venerated creative arts, and this did not change as Islamic influences helped to shape Mali. Education was also highly valued; Timbuktu was a significant center of learning with several prestigious schools. This intriguing blend of economic wealth, cultural diversity, artistic endeavors and higher learning resulted in a splendid society to rival any contemporary European nation.

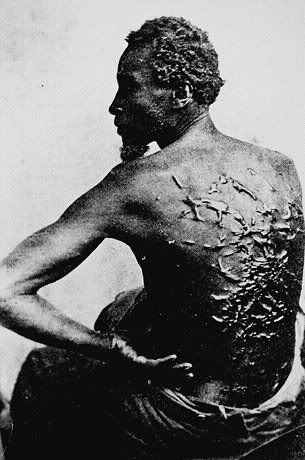

Malian society had its drawbacks, yet it is important to view these aspects in their historical setting. Slavery was an integral part of the economy at a time when the institution had declined (yet still existed) in Europe; but the European serf was rarely better off than a slave, bound by law to the land. By today's standards, justice could be harsh in Africa, but no harsher than European medieval punishments. Women had very few rights, but such was certainly true in Europe as well, and Malian women, just like European women, were at times able to participate in business (a fact that disturbed and surprised Muslim chroniclers). War was not unknown on either continent -- just as today.

After the death of Mansa Musa, the Kingdom of Mali went into a slow decline. For another century its civilization held sway in West Africa, until Songhay established itself as a dominant force in the 1400s. Traces of medieval Mali's greatness still remain, but those traces are fast disappearing as the unscrupulous plunder the archaeological remains of the region's wealth.

Mali is just one of many African societies whose past deserves a closer look. I hope to see more scholars explore this long-ignored field of study, and more of us open our eyes to the splendor of Medieval Africa.

MEDIEVAL AFRICA

From around AD 750 to 1500, lands to the south of Africa’s Sahara Desert were home to many thriving civilizations. Muslim kings ruled in cities like TIMBUKTU, and chiefs called OBAS were powerful in rainforest kingdoms. SWAHILI peoples became rich through trade.

HOW DID TRADERS CROSS THE SAHARA DESERT?

Traders from North Africa crossed the Sahara together in a group called a caravan. They led as many as 10,000 camels, heavily laden with goods, in a long line known as a camel train. At the southern edge of the Sahara, the goods were transferred to donkeys or human porters, to be carried farther south.

WHICH AFRICAN GOODS WERE HIGHLY PRIZED?

Gold, ivory, ebony, and slaves from West African kingdoms such as Ghana, Mali, and Songhai were sold in North Africa and the Middle East. They were traded for salt and copper, mined in the Sahara. Later, European traders came for gold, ebony, and slaves.

TIMBUKTU

Timbuktu (in central Mali) was one of the most important cities on the edge of the Sahara. After Muslim scholars brought the religion of Islam to the region, around 900, it became a great center of Muslim learning, with schools, a university, and a special market where valuable, handwritten books were sold.

HOW DID TIMBUKTU BECOME WEALTHY?

Like a number of other cities on the edge of the Sahara, such as Gao and Jenne, Timbuktu was also on the banks of the Niger River. These cities were inland ports. Merchants from the south sent boatloads of gold, ivory, cotton, dried fish, and kola nuts upriver to them, to be sold to people living there, or to be carried to lands farther north. Timbuktu became a terminus (end point) for one of the main trading routes crossing the Sahara.

WHY DID MUSLIM PILGRIMS GO TO TIMBUKTU?

Many Muslim pilgrims traveled to Timbuktu to honor the city’s 333 resident saints. These were celebrated Muslim scholars and teachers who taught their faith to people in the surrounding lands. Many beautiful mosques were built in Timbuktu.

SWAHILI

Swahili became the main language used by different peoples on the coast and islands of East Africa. Many of its words were taken from Arabic—the language of traders who sailed across the Indian Ocean, linking India and Arabia with East African ports such as Mogadishu, Gedi, and Kilwa.

WHO DID THE SWAHILI PEOPLES TRADE WITH?

East Africans produced valuable goods, such as leather, frankincense, leopard skins, ivory, iron, copper, and gold. They sold these to Indian Ocean traders. From around 1071, they sent ambassadors to trade with China, and, from 1418, welcomed Chinese merchant ships to East Africa’s ports.

ZANZIBAR

The island of Zanzibar, off the coast of East Africa, is where Swahili was first spoken. It became a major trading center for slaves, ivory, and cloves.

OBAS

From around 1250 to 1800, a number of different kingdoms made up what is now southwest Nigeria, in West Africa. Each of these was ruled by an oba. The obas were both religious and political leaders. Their subjects, the Yoruba people, lived as farmers, and built city-states surrounded by massive walls of earth.

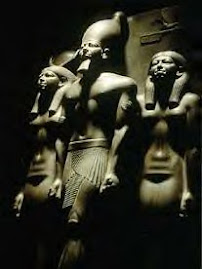

WHERE WERE MANY STATUES OF OBAS MADE?

People living in the rainforest kingdom of Benin, now in south Nigeria, were expert metalworkers and cast elaborate portrait heads of their obas, as well as decorative plaques and ceremonial objects. These were made from brass or bronze and were used for ancestor worship, or to decorate the rulers’ palaces.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE KINGDOMS OF THE OBAS?

The power of the obas and other African rulers was weakened by the arrival of Europeans. Portuguese, Dutch, and British traders took back news to their countries of the riches of Africa. Explorers were encouraged to travel there and, by 1900, almost all of Africa was ruled by European powers.