“Ten Little Niggers”: The Making of a Black Man’s Consciousness

Tiffany M.B. Anderson

The Ohio State University

Abstract:

During Reconstruction in the 1860s, the proud Confederate states found themselves in a place of subordination. Forced to concede their free slave labor, the former citizens of the Confederacy refused to fold their ideology of the inferiority of the freed slaves. A “comic” song titled “Ten Little Niggers” circulated through the United States in Minstrel shows and children’s nursery rhyme books in keeping with this ideology.

This paper explores how the ballad shapes social and cultural race consciousness. While the purpose of its widespread popularity was to refute the competency and human qualities of the black freedmen to white audiences, the ultimate legacy that the rhyme leaves behind is the mental conditioning of following generations of black males. The white population who circulated the song intended to define the black freedmen as barbaric and ignorant, yet the song also connected the white-constructed definition of ‘nigger’ to the black man’s consciousness.

The United States was a nation undergoing destruction and reconstruction in the 1860’s. Towards the end of the Civil War, President Lincoln agreed to gesture the freeing of all African slaves through the Emancipation Proclamation. Even as they found themselves in a position of subordination, forced to concede their free slave labor for the Union’s promise to reconstruct their ruined lands and severed ties to the North, the former citizens of the Confederacy refused to compromise their ideology of the freed slaves’ inferiority. In fact, folklore developed to further propagate the belief of black inferiority. A “comic” song titled Ten Little Niggers circulated through the United States in minstrel shows and children’s nursery rhyme books typical of the proliferation of materials focused on the degradation of the African American race.

In this paper I am interested in how this song shapes social and cultural race consciousness. While the purpose of its widespread popularity was to refute the competency and human qualities of black freedmen to white audiences, the ultimate legacy of the minstrel song and nursery rhyme is the mental conditioning of black males. It is the essence of this mental conditioning that I hope to explore. The white population who circulated the song intended to characterize the black freedman as barbaric and ignorant, and the song also connected the white-constructed definition of ‘nigger’ to the black man’s consciousness.

The minstrel show was popular even before the Civil War, performed before audiences in both the North and the South. However, the shows’ materials changed once freedom was granted to the Negro slaves in the United States. Before the matter of freed slaves became a volatile issue, the typical minstrel show exhibited white men in black makeup performing song and dance exaggerated by lack of coordination and improper English, a style that became known as Jim Crow. After the Civil War, the stage opened itself up to new performers, recently freed slaves, willing to impersonate the impersonator. These performers, though already darker skinned, adhered to the minstrelsy tradition of blackface makeup. The tone of these black caricatures became less innocent and more damaging to blacks. The shows evolved from Jim Crow shows to coon shows, which focused on the wily nature of the freed slave. Black theater scholar Eric Lott notes that “the coon show was a mine of problematic racial representations, from razor-toting hustlers and gamblers to chicken-thieving loafers” (Lott 172). It is in the midst of these popular coon shows that the minstrel song Ten Little Niggers enters the stage. This comic song married the stereotypes of violence and ignorance of blacks in order to villanize freed black males while allowing the violence to be acted upon the black players of the song. I will focus on the following version of the rhyme for my analysis:

Ten little nigger boys went out to dine;

One choked his little self and then there were Nine.

Nine little nigger boys sat up very late;

One overslept himself and then there were Eight.

Eight little nigger boys travelling in Devon;

One said he’d stay there and then there were Seven.

Seven little nigger boys chopping up sticks;

One chopped himself in halves and then there were Six.

Six little nigger boys playing with a hive;

A bumble bee stung one and then there were Five.

Five little nigger boys going in for law;

One got into Chancery and then there were Four.

Four little nigger boys going out to sea;

A red herring swallowed one and then there were Three.

Three little nigger boys walking in the Zoo;

A big bear hugged one and then there were Two.

Two little nigger boys sitting in the sun;

One got frizzled up and then there was One.

One little nigger boy left all alone;

He went out and hanged himself and then there were None.

Ten Little Niggers surfaced in two distinct genres: minstrel shows and children’s nursery rhymes. While the words usually remained the same in both genres, the audience varied greatly in age. The audience of the minstrel shows was typically white adult Americans indulging in the popular form of mainstream entertainment and, especially during this time, entertainment weighed heavily in the transmission of racial conditioning. While periodicals in Great Britain, for example, advertised the song as a comic song, the stereotypes created and spread through the largely popular genre of the minstrel show were anything but comic and in fact furthered the dehumanization of the recently freed black population (“The London Theatres”). The live performances of Ten Little Niggers in minstrel shows allowed the white audience to face a living manifestation of their fears in comic form. The act of chiding the black race became an empowering act of watching black or blackface performers denounce themselves in a public forum.

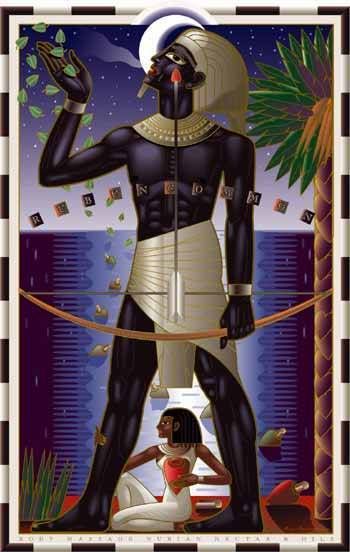

The appearance of the ballad in children’s nursery rhyme books represents the early racist indoctrination of children. When performed as a minstrel song, Ten Little Niggers serves as entertainment; when used as a nursery rhyme, Ten Little Niggers operates as education. Ten Little Niggers not only taught a child to count down from ten, it also presented the racial construction of the black population as ‘niggers’ with equal importance. Caricatures accompanied the reprinting of the song in the nursery rhyme books. The pictures varied from edition to edition, but all were grossly exaggerated cartoons of black males. In the first publication of 1875, made available by the McLoughlin Brothers, the cover shows the ten main characters dressed alike in sailor shirts and enjoying the music of the banjo that one of them plays (Martin 21, 22). Because the McLoughlin version of the book also includes the sheet music that accompanies the rhyme, “readers might assume that these characters are singing the story. In this case, they are celebrating their own demise” (Martin 21). The pictures support this analysis in that the characters remain smiling and laughing on each page. Though the many publications of the same rhyme boast different pictures, the basis of the characters remains the same. The “little niggers” are really men with the same face watching as each die violent, unusual, and, mostly, unnecessary deaths one by one. One of the only changes in the actual text in the children’s nursery rhyme comes with the final character. For nearly two decades, the last character dies just as the others had: sometimes he gets “frizzled up” in the sun, other times he hangs himself . In 1894, McLoughlin Brothers revised their commercial success so that the last “little nigger” marries. And while original copies of these nursery rhyme books are difficult to find in the United States, the skeleton of the nursery rhyme still exists in the education of American children. Ten Little Niggers became Ten Little Indians. Upon the race movements of American Indian people that contested the (mis)representations of American Indians in American folklore and contemporary culture, the nursery rhyme became Ten Little Soldiers.

It is easy to read the minstrel song today and recognize the stereotypes that are evoked. Black people eat and sleep with nothing else in their day; they senselessly participate in activities such as “playing with a hive” that common sense teaches most people is not a proper pastime; they prove burdensome to the legal system; they are, at best, lesser evolved creatures, closer to animal kind than mankind. These stereotypes live in the American consciousness today, but when the song was popularized, the racialized American psyche was still in the creation process. In addition, African Americans were processing understandings of self outside of the debilitating institution of slavery that rejected self-determined identities. The song taught white Americans how to view subjects that were previously objectified in the cloak of slavery and taught blacks how to view themselves through the perspective of white Americans.

Reading the historical song with a modern perspective, one finds a general analysis commonsensical. The stereotypes upon which the song depends appear trite, but there are several stanzas that require a closer analysis. The character who chooses to stay behind in Devon, for example, is not simply explained by a recognizable stereotype:

Eight little nigger boys travelling in Devon;

One said he’d stay there and then there were Seven.

The character’s status changes from tourist to immigrant within the two lines dedicated to his journey. The character’s resolution to stay in the English county alarmed the contemporary listeners of the song: the decision marks an invasion by black people of white land. The former slaves’ freedom to travel and freedom to choose threatened the white audiences’ comfort zone. Migration of black males was acceptable if for the sake of slavery, but the migration of black freed males suggested equality that white people of this time were not prepared to face.

The only character who performs labor in the ballad works himself to death:

Seven little nigger boys chopping up sticks;

One chopped himself in halves and then there were Six.

It is significant that he is not doing the work typical of a field slave. If he were to die in a cotton field, the song’s attack against slave emancipation would fail. This stanza demonstrates the dangers of an ignorant, sub-human being with a weapon and operates as warning against hiring blacks and a verification of white people’s fears. The stanza advises against giving small tasks such as wood chopping to freed slaves. Through this caution, the economic status of freed slaves is threatened, especially considering that most employment opportunities for blacks during Reconstruction came from whites. Furthermore, the stanza reinforces the previous characterizations of black men carrying knives that were also popular in minstrel shows. Here, even a working tool in the hand of a ‘nigger’ becomes a weapon. This idea is complicated by the fact that the tool is a weapon against the carrier of the weapon. Self-inflicted injuries with the ax is not purposeful in this case which suggests that while the black man is dangerous, his incompetence makes for an even more frightening case: bloodshed results from both the violent intent and unintentional simple-mindedness.

The fourth “nigger boy” dies in the belly of a red herring:

Four little nigger boys going out to sea;

A red herring swallowed one and then there were Three.

The choice of fish here is key. The red herring carries multiple connotations. The Oxford English Dictionary cites a usage in the 16th century that notes the in-betweenness of the red herring: “they that are neither of both, but betwixt both, neither Fish nor Flesh, but plaine [sic] Red-Hearing” (OED). The in-betweenness of the red herring points to the in-betweenness of the black male. Whites struggled with naming blacks: they were neither animal nor human. The stanza also invites us to read the red herring in its common metaphorical use to reference distraction, specifically in allusion to the Civil War. Although constructed as a war about slavery, the Civil War played out with greater political and economic issues for both the Union and the Confederacy. Slavery and, consequently, the Emancipation Proclamation were mere diversions. When the red herring in the poem swallows the black man, he eliminates the diversion which allows attention to return to the larger issues at stake, state governance versus federal governance.

The third character to die is murdered by affection: a bear hugs him to death. This stanza recalls the question of humanity as it relates to the black male. The bear does not attack him or view him as a threat as he would a human being; rather the bear sees a likeness within the “little nigger.” The black male, therefore, receives a more affirming response in a zoo than he does in the world among humans.

The final death is a suicide:

One little nigger boy left all alone;

He went out and hanged himself and then there were None.

This character is the only out of the nine to die who dies purposefully instead of accidentally. The song points to the isolation of the last character as the reason for the suicide, yet the most significant detail of this final stanza is in how the “little nigger” chooses to die. He takes notice from the lynch law of the South and hangs himself. While this method of suicide might simply suggests an echo of the mistreatment of blacks in the Post-bellum South, I contend that this final character’s death demonstrates black adoption of white American perspective regarding black life and black death.

The song acts as a fantasy for those who enjoyed performances. While whites wondered what to do with the freed slaves, the song suggested that leaving them alone to destroy themselves was the best method. The comedic intent of the song seems haunting to today’s listener and encourages one to question the humor of nine deaths in ten stanzas. To better understand the humor, we can turn to a similar kind of dark humor in folklore: dead baby jokes. Alan Dundes explains, “the most obvious interpretation of the cycle would seem to be a protest against babies in general” (Dundes 154). This theory is quite applicable in our analysis of the song Ten Little Niggers. The cycle of the song serves as a protest against freed black men. As demonstrated in the song, the deaths all result due to the freedom of black men, and the song only surfaced in response to the freeing of slaves. The unspoken point behind the song is that nothing in the song would happen if the institution of slavery were still legal. Black men were needed for free labor in the Antebellum South and were controlled by white masters and, therefore, protected against themselves. To word it a bit differently, black male slaves were safe from themselves as was the rest of the world, specifically, and most importantly, white men and women.

Ten Little Niggers becomes one of the first clear definitions of nigger as a derogatory term. Originally, the negativity that ‘nigger’ evoked came from the tone and attached ideology of the person saying it. While value judgments might have existed within the first people who used the word ‘nigger,’ the original use of ‘nigger’ was merely to identify the new Africans on American soil:

Most lexicographers trace both words to “niger,” the Latin word for “black.” Some of them also contend that “nigger” was intended initially as a neutral term [ . . .] the word acquired a derogatory character over time, picking up various spellings along the way (Asim 10).

Although nigger carried negative connotations for those who used the word and for those who were called the word, the transformed understanding of what a nigger was remained undocumented until Ten Little Niggers clearly demonstrated the ignorance, slothfulness, and violence of black men that was once simply understood.

While the perpetuators of the song were mostly white, black people came to know the song as well. Perhaps black minstrels sung the tune at shows; young black children encountered the rhyme in magazines like St. Nicholas (Johnson-Feelings 134). The extraordinary transference of the stereotypes occurred once the term nigger, often used to address these freed blacks, was clearly defined. And the negative depiction of niggers that the song presented became real for the grossly misrepresented black male. According to scholar Barbara Christian in an interview found in the documentary Ethnic Notions, the stereotype becomes a part of one’s consciousness:

[People] believe these images because [they have] become [threads] throughout the major fiction, film, popular culture, the songs, even the jokes black people make about themselves. It has become a part of our psyche. It’s a real indication that one of the best ways of maintaining a system of oppression has to do with the psychological control of people.

Because white Americans saw black men as the “little nigger boys” in the song, the black men began to see themselves this way also. As Christian notes, “our lives are lived under that shadow [of these stereotypes] and sometimes, we then even come to believe it ourselves.” In The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois introduces double-consciousness as a “peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amusement, contempt and pity” (Du Bois para. 3). Once this definition of nigger becomes real for black men, the black men mirror the definition represented within the song: black men begin to act out the slothfulness, ignorance and violence of the characters within Ten Little Niggers.

The freed black men were refused a consciousness previous to their emancipation. Everything that their ancestors knew was left behind in Africa because slave masters severed cultural connections. Toni Morrison suggests that for American white settlers, “the attraction was of the ‘clean slate’ variety, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity not only to be born again but to be born again in new clothes” (Morrison 34). For the African slaves, the clean slate was forced upon them and the choosing of what would be wrought on the new slate was not their own. Due to the explosion of nigger representations in the Reconstruction Era of America, the nigger mentality soiled the clean slate of freed men searching for a new identity. Once freedom presented itself, the black males’ identity remained dangerously in the hands of white Americans, and the white Americans decided black men would be niggers.

No comments:

Post a Comment