Shem Hotep ("I go in peace").

"We cannot be equal with the master until we own what the master owns. We cannot be equal with the master until we have the education the master has. Then, we can say, "Master, recognize us as your equal."

Elijah Muhammad (1897-1975)

Puerto Rican people.

A Puerto Rican (Spanish: puertorriqueño) (Taíno term: boricua) is a person who was born or raised in Puerto Rico.

Puerto Ricans born and raised in the United States are also referred to as Puerto Ricans, although they are not native Puerto Ricans, but descendants of Puerto Ricans. Rarely are Puerto Ricans born in the diaspora called Puerto Rican Americans, or simply Americans.

Puerto Ricans, who also commonly refer to themselves as "boricuas", are largely the descendants of Europeans, Taíno, Africans or a blend of these groups which has produced a very diversified population. The population of Puerto Ricans and descendants is estimated to be between 8 to 10 million worldwide, with most living within the islands of Puerto Rico, Central Florida, Chicago Metropolitan Area and in New York City, where there is a large Nuyorican community.

For 2008, the American Community Survey estimates give a total of 3,846,054 Puerto Ricans classified as "Native" Puerto Ricans. It also gives a total of 3,638,484 (92%) of the population being born in Puerto Rico and 195,506 (4.9%) born in the United States. The total population born outside Puerto Rico is 315,553 (8%).

Of the 107,983 who were foreign born outside the United States (2.7% of Puerto Rico), 5.2% were born in Europe, 92.7% in Latin America, 2.0% in Asia, 0.2% in Northern America, and 0.0% in Africa and Oceania each.

Race and ethnicity.

Whites.

Spanish immigration to Puerto Rico:

White Puerto Ricans of European, mostly Spanish descent, are said to comprise the majority with 80.5% reported in the 2000 United States Census. For the first time in fifty years the 2000 United States Census asked people to define their race. In 1899, one year after the U.S invaded and took control of the island, 61.8% of people identified as White. One hundred years later, the total was to 80.5% (3,064,862), less than one percent more than reported in 1950. The European heritage of Puerto Ricans comes primarily from one source: Spaniards (including Canarians, Catalans, Castilians, Galicians, Asturians, Andalusians, and Basques).

The Canarian cultural influence in Puerto Rico is one of the most important components in which many villages were founded from these immigrants, which started from 1493 to 1890 and beyond. Many Spanish, especially Canarians, chose Puerto Rico because of its Hispanic ties and relative proximity in comparison with other former Spanish colonies. They searched for security and stability in an environment similar to that of the Canary Islands and Puerto Rico was the most suitable. This began as a temporary exile which became a permanent relocation and the last significant wave of Spanish or European migration to Puerto Rico. Other sources of European populations are Corsicans, French, Germans, Irish, Portuguese, Scots, Maltese, Italians and Jews, with many Arab Christians such as the Lebanese and Palestinians.

Sub-Saharan African/Black

Black history in Puerto Rico:

Today 8.0% of people self-identified as Black in the last 2000 United States Census. Immigration of African free men who arrived with the Spanish Conquistadors, the vast majority of the Africans who immigrated to Puerto Rico did so as a result of the slave trade from many different areas of the African continent. Such as West Africans, the Yoruba and the Igbo people.

Amerindian Mestizos, Amerindian, and Taino.

Amerindians and Mestizos are those who have a pure Amerindian descent or mixed ancestry between Europeans and Amerindians within the Puerto Rican context discarding the other definitions that this term may be used for under other settings. Amerindians make up the third largest racial identity among Puerto Ricans comprising 0.4% of the population.

Abolition of Slavery in Puerto Rico.

Former slaves in Puerto Rico, 1898

Indemnity bond paid as compensation to former owners of freed slaves

On March 22, 1873, slavery was abolished in Puerto Rico. Slave owners were to free their slaves in exchange of a monetary compensation. The majority of the freed slaves continued to work for their former masters with the difference that they were now freeman and received what was considered a just pay for their labor.

The freed slaves were able to fully integrate themselves into Puerto Rico's society. It cannot be denied that racism has existed in Puerto Rico since racism is something that may exist in anyone's heart; it is impossible to know. However, racism in Puerto Rico did not exist to the extent of other places in the New World, possibly because of the following factors:

• In the 8th century, nearly all of Spain was conquered (711–718), by the Muslim Moors who had crossed over from North Africa. The first blacks were brought to Spain during Arab domination by North African merchants. By the middle of the 13th century all of the Iberian peninsula had been reconquered. A section of the city of Seville, which once was a Moorish stronghold, was inhabited by thousands of blacks. Blacks became freeman after converting to Christianity and lived fully integrated in Spanish society. Black women were highly sought after by Spanish males. Spain's exposure to people of color over the centuries accounted for the positive racial attitudes that were to prevail in the New World. Therefore, it was no surprise that the first conquistadors who arrived to the island, intermarried with the native Taínos and later with the African immigrants.

• The Catholic Church played an instrumental role in the human dignity and social integration of the black man in Puerto Rico. The church insisted that every slave be baptized and converted to the Catholic faith. In accordance to the church's doctrine, master and slave were equal before the eyes of God and therefore brothers in Christ with a common moral and religious character. Cruel and unusual punishment of slaves was considered a violation of the fifth commandment.

• When the gold mines were declared depleted in 1570 and mining came to an end in Puerto Rico, the vast majority of the white Spanish settlers left the island to seek their fortunes in the richer colonies such as Mexico and the island became a Spanish garrison. The majority of those who stayed behind were either black or mulattos (of mixed race). By the time Spain reestablished her commercial ties with Puerto Rico, the island had a large multiracial population, that is up until the 1850s, when the Spanish Crown put the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 into effect which "whitened" the island's population by offering attractive incentives to non-Hispanic Europeans. The new arrivals continued to intermarry with the native islanders.

The racism that did exist and which Black Puerto Ricans were subject to was exposed by two Puerto Rican writers; Abelardo Diaz Alfaro (1916–1999) and Luis Palés Matos (1898–1959) who was credited with creating the poetry genre known as Afro-Antillano

Abelardo Diaz Alfaro

Luis Palés Matos

Notable Puerto Ricans of African Ancestry.

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, also known as Arthur Schomburg, (January 24, 1874 –June 8, 1938), was a Puerto Rican historian, writer, and activist in the United States who researched and raised awareness of the great contributions that Afro-Latin Americans and Afro-Americans have made to society. He was an important intellectual figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Pedro Albizu Campos (June 29, 1893 or September 12, 1891 – April 21, 1965) was a Puerto Rican politician and one of the leading figures in the Puerto Rican independence movement. He was the leader and president of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party from 1930 until his death. He was imprisoned for many years, on several occasions, in both United States and Puerto Rico, dying shortly after his release from federal prison. Because of his oratorical skills he was known as El Maestro ("The Teacher").

Roberto Clemente Walker (August 18, 1934 – December 31, 1972) was a Puerto Rican professional baseball player and a Major League Baseball right fielder.

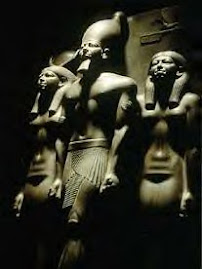

Akhenaton (1375-1358 B.C.)

Amenhotep IV, better known as "Akhenaton, the Heretic King," is in some respects, the most remarkable of the Pharaohs. After the death of his father, he came into full power in Egypt and took the name Akhenaton. He produced a profound effect on Egypt and the entire world of his day.

Thirteen hundred years before Christ, he preached and lived a gospel of perfect love, brotherhood, and truth. Two thousand years before Mohammed, he taught the doctrine of the "One God." Three thousand years before Darwin, he sensed the unity that runs through all living things.

The account of Akhenaton is not complete without the story of his beautiful wife, Nefertiti. Some archaeologist have referred to Nefertiti as Akhenaton's sister, some have said they were cousins. What is known is that the relationship between Akhenaton and Nefertiti was one of history's first well-known love stories.

At the prompting of Akhenaton and Nefertiti, the sculptors and the artists began to recreate life in its natural state, instead of the rigid and lifeless forms of early Egyptian art.

Althea Gibson (August 25, 1927 – September 28, 2003)

Althea Gibson, who moved with her family to Harlem at the age of three, was from an early age involved in many competitive sports. Gibson began to play tennis in Police Athletic League paddle tennis games. In 1945, she won the girls' singles championship of the all-black American Tennis Association (ATA), and from 1947 to 1956, she held the title for the ATA women's singles. In 1946, Gibson moved to North Carolina to live with Dr. Hubert Eaton, who, along with Dr. R. Walter Johnson, took an interest in her career. Under their tutelage, Gibson's game matured, and she developed her fast footwork and signature big serve.

In 1953, Gibson graduated from Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. During the 1950s, she began to challenge racial segregation in tennis by playing at tournaments sponsored by the United States Lawn Tennis Association (later renamed United States Tennis Association), which had previously been restricted to white players. In 1950, Gibson became the first black competitor at the National Championships (later renamed the U.S. Open) in Forest Hills, New York. She was invited to compete only after Alice Marble, a four-time singles winner at Forest Hills, expressed her disgust at the efforts to stop Gibson from playing because of her race. In 1951, Gibson was the first black person to play tennis at the Lawn Tennis Championships at the All-England Club in Wimbledon, England.

Gibson's game slowed down in the early 1950s, at which point she worked as a physical education teacher in Missouri for two years. However, her game was revitalized by a tennis tour of Southeast Asia organized by the U.S. State Department in 1955. In 1956, Gibson won the women's singles championship at the French Open Tournament and then went on to win both the women's singles and doubles championships at Wimbledon and the U.S. National Championships at Forest Hills in 1957. In the same year, the Associated Press honored Gibson with the Female Athlete of the Year award. In 1958, she repeated her victories in the women's singles at both Wimbledon and Forest Hills.

Gibson retired from competitive tennis in 1959, turning her attention to other interests. During the 1960s, Gibson played professional golf, joining the U.S. Ladies Professional Golf Association in 1963, although she did not have the same success with golf that she had had with tennis. Gibson worked for the New Jersey state sports commission during the 1980s, and lectured and taught clinics on tennis. In 1971, she was elected to the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

During the 1990s, Gibson attempted a golf comeback and continued to speak about tennis and physical fitness in general. She authored two books: I Always Wanted to Be Somebody (1958) and So Much to Live For (1968).